Cae la ceniza sobre mi mano y el instante es egipcio…

David Huerta

“La historia de la pintura moderna -escribe Octavio Paz en La apariencia desnuda. La obra de Marcel Duchamp-, desde el Renacimiento hasta nuestros días, podría describirse como la paulatina transformación de la obra de arte en objeto artístico”, para señalar un poco más adelante: “El valor de un cuadro, un poema o cualquiera otra creación de arte se mide por los signos que nos revela y por las posibilidades de combinarlos que contiene. Una obra es una máquina de significar”.

Los trabajos del pintor, como los del poeta, se asemejan en más de un sentido, buscan dotar de significado las piezas que producen, darles una vida más allá de las intenciones ocultas de quien las crea, otorgarles un poder para trascender y tocar el espíritu de cualquiera que las mire, las contemple, las asimile como propias.

Los trabajos de William Berry, sea en la tela o en el papel, en la piedra, en la placa o en el jardín, luchan permanentemente contra esta doble condición, la ilusión de la obra como objeto y la tentación de la máscara del artista, la idea de que el producto artístico es lo que vale la pena conservar, mostrar, comprar y vender, y la tentación de ser un productor de objetos coleccionables por otros. Pero para el artista el proceso lo es todo, la obra estará siempre definitivamente inacabado en tanto no se encuentre con su espectador, con su público. Quizá por esto la fuente principal de ideas y recursos, de energía y de fuerza para Will Berry sea la naturaleza, el entorno, el aire que respira, los signos en rotación.

Su trabajo, desde que se levanta hasta que vuelve a la cama, transcurre en una evolución hacia el arte de la combinatoria, de la búsqueda de significación hacia y desde el mundo que lo rodea, de ahí que su terraza en la colonia Roma se esté convirtiendo en un jardín de las ideas, un espacio para que la mente pueda desbocarse y lanzar sus redes hacia la reflexión sobre los pasos que hacen del artista un nómada, un caminante.

En esta dinámica en que vive el artista contemporáneo, Will Berry se sacude su sombra y da un paso al costado, sale de sí mismo, de su mundo occidental, y se lanza a la aventura de ser otro, un nuevo artista que no quiere confundir su trabajo con el trabajo del pintor, su obra con la obra que se espera de él. Prueba de ello es su obsesión por las servilletas, un trabajo meticuloso y sistemático que ejerce desde hace 20 años y que se ha convertido en una bitácora, una memoria de los sitios donde ha estado, vivido, soñado, un recuento de los días y las horas que se han cruzado por su mirada, la del dibujante que se entrega al placentero oficio de la contemplación absoluta.

Pero también es una prueba de su relación con el aquí y el ahora, una necesidad por anclar todo lo que es en un momento determinado en el espacio, como si en esos trozos de papel fijara su piel y sus ideas gracias a la absorción de la tinta sobre las superficies más delgadas y quizá insignificantes . Nuevamente, insignificancias en búsqueda de significado, significación, signos, puntos para fijar la mirada y aterrizar una mente en rotación.

La serie que aquí presenta es un ejemplo de su pasión por el dibujo, por la creación en todos lados y en todo momento, un puñado de servilletas seleccionadas de entre una decena de cajas rebosantes de papeles, recolectados a lo largo de los años en restaurantes y cafés de varias ciudades del mundo, un trozo de su memoria que, a final de cuentas, es un trozo de la memoria colectiva.

El título de esta serie pudo ser Bajo la Montaña Negra (Below the Black Mountain), en una clara alusión tanto al libro de Lowry como al suceso emblemático de la Black Mountain School, pero también pudo ser El corazón de la Piedra Negra (The Heart of the Black Stone), o un poco más allá, Desde las cenizas (From the Ashes). ¿Por qué? Porque esta pequeña serie es resultado del radicamiento de Will Berry en la Ciudad de México, y sobre todo, de su apropiamiento del sur de la ciudad y de sus piedras negras y volcánicas.

Una investigación exhaustiva en la vida y obra de este pintor arrojaría sin duda información sobre sus modos de ver y de escuchar, sin mencionar su particular estilo de hablar, por lo bajo, casi en un susurro, como fijando una posición que apuesta por el sentido y la esencia de lo que se dice más que por la forma o la potencia. El valor y la fortaleza del mundo están en su interior, y si bien es importante mostrar un cierto poder al expresarlos, es un hecho que el misterio y el silencio se asocian con mayor facilidad a la serenidad y al equilibrio.

Al escribir estas líneas pienso en la posible relación entre las palabras y los signos expuestos por Will en sus servilletas, y sobre todo, en la importancia que tienen estas piezas en el corpus de su obra, en la historia personal que ha dibujado en los últimos 20 años. Desde las cenizas se antoja como el título más adecuado para encontrar afinidades con su trabajo, pues el suyo es el proceso del Fénix, que se alza de las cenizas en una nueva aventura vital que comienza al mudarse a la Ciudad de México.

La suya parece una resurrección, un volver a la vida para honrar el momento, Carpe Diem, para honrar la amistad, la creación, la charla. La suya parece una existencia levitativa que sólo aterriza para hacer concretas las obras que forman su catálogo personal, los cuadros, los grabados, las plantas, las raíces, los pocos muebles que habitan junto con él el espacio vital.

Aparece este libro y es de celebrar por más razones que la obvia. Los libros de artista, de autor, los libros-objeto, están desapareciendo. Celebro que Chichicatle Art Press nos muestre un camino a seguir, difícil de recorrer ciertamente, pero caminable. Un camino con corazón, como decía Castaneda que decía Don Juan, aunque ambos fueran sólo una raya en el agua, un camino para reconocemos en él, para templamos, para encontrar un mejor lugar en el mundo. William Berry encuentra con este libro y con sus piezas, con su trabajo y sus amigos, con su esmero y su dedicación, un mejor lugar en el mundo.

Sabe que no hay tregua, que este lugar existe sólo si él lo hace todos los días, como explica la Física Cuántica, el mundo es lo que nosotros queramos que sea, como queramos, cuando lo queramos, ésa es la lección que se repite a sí mismo William Berry y que registra en su trabajo todos los días.

http://bacaanda.blogspot.com/2007/02/desde-las-cenizas.html

From the ashes

Translation by Belinda Duckles

Cae la ceniza sobre mi mano y el instante es egipcio

David Huerta

In his book La apariencia desnuda. La obra de Marcel Duchamp, Octavio Paz wrote: ”The history of Modern Art, from the Renaissance to our days, can be described as the gradual transformation of the work of art into an artistic object”, to point out later on: “The value of a painting, a poem or any other artistic creation is measured by the signs it reveals to us and their possible combinations. A work of art is a signifying machine¨.

The works of an artist, like those of a poet, are similar in many ways; they seek to render meaning to the pieces they produce, to give them life beyond the hidden intentions of the creator, granting them the power to transcend and touch the spirit of whoever sees them, observes them and assimilates them unto himself.

The works of William Berry, whether on canvas or paper, stone, plates or in the garden, are permanently struggling against this double condition, the illusion of the work as an object and the temptation of the artist’s mask, the idea that the artistic product is what is worth preserving, showing, buying or selling; the temptation to produce objects for others to collect. For the artist all is in the process, the work will always be definitively unfinished until it has met with it’s spectator, it’s public. Maybe this is why, for Will Berry, the main source of ideas and resources, energy and strength, is in nature, in his surroundings, in the air he breathes, in the rotating signs.

From the moment he wakes until he goes back to bed his work occurs in an evolution towards the art of combinations, the search for meaning towards and from the world that surrounds him; this is why his terrace on the colonia Roma is becoming a garden of ideas, a space where the mind can run wild thrusting its nets towards a reflection on the steps that turn the artist into a nomad, a traveler.

In this dynamic that is inhabited by contemporary artists, Will Berry shakes free of his shadow and steps aside, abandoning himself, his Western world, and throwing himself into the adventure of being an Other, a new arts that does not wish his work to be mistaken with the work of the artist, his ouvre with what is expected from him. Proof of this is his obsession with napkins, a meticulous and systematic work he has been practicing for 20 years, and that has become a logbook, a memoir of the places where he has been, lived, dreamed; an inventory of the days and hours that have crossed his gaze, of the sketcher who surrenders himself to the pleasant trade of absolute contemplation.

It is also, however, proof of his relationship with the here and now; a need to anchor all, a certain moment in space that can be, as if through the absorption of ink on the thinnest, maybe most insignificant, surfaces, as if he were fixing his skin and his ideas in those pieces of paper. Again, insignificances in search of meaning, signification, signs, and points in which to fix the gaze and land a rotating mind.

This series exemplifies his passion for drawing, for creating anywhere, anytime. From a handful of napkins selected from a dozen boxes brimming with pieces of paper, collected along the years in restaurants and cafes of various cities in the world, one takes a piece of his memory that, ultimately is a piece of collective memory.

The title of the series, which originates this book, could have been Below the Black Mountain, Clearly alluding to Lowry’s book, as well as the emblematic Black Mountain School, but it could also have been The Heart of the Black Stone, or beyond that, From the Ashes. Why? Because this small series is the result of Will Berry’s residing in Mexico City and, above all, his appropriation of this country, its images, its being and its signs; southern Mexico City and its black, volcanic stones.

An exhaustive research into the life and work of this artist would undoubtedly shed more information about his way of seeing and listening, no to mention his particular way of talking in a low voice, almost a whisper, as if he was establishing a position that emphasizes the sense and the essence of what is said rather than it’s form or potency. The value and strength of the world are within it, and even though it is important to demonstrate certain power when expressing them, it is a fact that mystery and silence are more readily associated with serenity and equilibrium.

While I write these lines I reflect on the possible relationship between the words and the signs exposed by Will in his napkins and, above all, on the importance of these pieces in the corpus of his work, in the personal history he has drawn during the last 20 years. From the Ashes feels like the most adequate title to find affinities with his work, for his process is that of the Phoenix that rises from the ashes in a new vital adventure that began when he moved to Mexico City.

His, seems like a resurrection, a coming back to life to honor the moment, Carpe Diem, to honor friendship, creation, conversation. His, seems a levitational existence that only lands long enough to make concrete the works that shape his personal catalogue, the paintings, engravings, plants, roots, the few pieces of furniture that co-inhabit this vital space

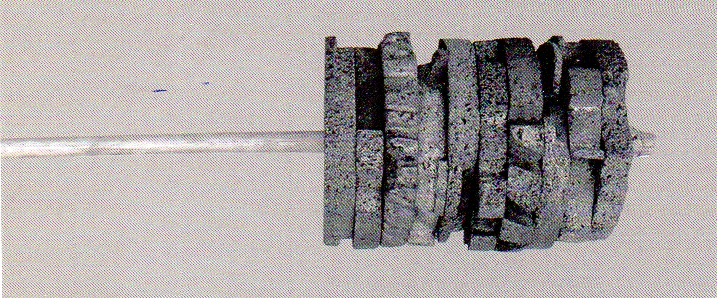

This book, The Pull of the Air, appears under the editorial seal of Taller Raiz (sister company of Chichicastle Art Press), and must be celebrated for reasons beyond the obvious. Books on artists, author-based, object-books, are disappearing. I celebrate that Taller Raiz is showing us a road to be followed, hard to traverse, certainly, but walkable. A road with heart, as Carlos Castaneda said Don Juan Matus used to say, even though both were just a line drawn in water, a road where to meet ourselves, to temper us, to find a better place in the world. In conversation, William Berry said: “In Pull of the Air, we were able to create a series of original engravings with the skill of master engraver Eric Muñoz, who reproduced 10 of napkin drawings using a process in which the image is transferred directly onto the coppe plate¨. In this book and in his art, in his work and in his friendships, William Berry finds abetter place in the world.

Will knows there is no rest; this place only exists if he recreates it every day. As Quantum Physics explains, the world is what we want it to be, like we want it, when we want it, and that is the lesson that William Berry repeats to himself, and is daily registered in his work.